In the office we work with our backs to televisions; typing, flicking through webpages, picking up phones. Typing. Behind our backs, pictures flash and headlines shout, unbeknownst, until someone turns around to reach for a book or a cardigan. Then, one day, you hear an audible intake of breath, or, if it's bad enough to warrant sharing, an utterance, an 'Oh my god', a low, awe-laden 'wow'.

Surely never a mystical instinct or an overwhelming sudden awareness of distant human suffering forces us to turn to 24-hour news and catch a breaking feed, the ticker tape of doom so unequal to its task, so mocking of our attempts to track tragedy, all over the world, now, as it happens now, and now.

Nevertheless, someone will glimpse capital letters on a red banner at the bottom of the screen, and sooner or later we will feel the need to stand around one television, for it is better to digest traginews en masse, to swear under our breaths but just loud enough to make ourselves heard, to feel the visceral thrill of knowing some kind of history is being made, and to believe, inanely, that by watching a screen, we are somehow present.

When the news broke that a number of university students had been shot by a gunman in Virginia, U.S.A, we were working on other stories. That week's international magazine cover was to have been some timely comment on European politicians; I had been asked to research a gently worshipful piece about the Queen. All were pushed to one side by the enormity of the Virginia story; a story that seemed to call to editors by name, demanding grand, funereal gestures; a new, black cover, numerous interactive build-out features online, a sombre, horrified, aghast tone.

There had been a tragedy. Terrible loss on a large scale and in horrific circumstances. Panic and terror and pain, all too easily imaginable. And yet.

As the self-reflexive media would eventually point out in the days to follow, 33 dead would have been a moderate to good day in Iraq. iraqbodycount.org reports 34 civilian dead on the 7th of April, 56 dead on the 6th of April. On the 18th April, 140 "shoppers, vendors in market and construction workers, commuters" were killed in Sadriya market, Baghdad. 4 times as many as had died that day in Virginia Tech.

And every single day, for weeks, months, years, Iraqi innocents are dying. As Polly Toynbee shouted through the vacuum, "THEY BELONG TO US!" (http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/story/0,,2061826,00.html), for "This is our war, our fault, our bloodshed for aiding America's reckless and incompetent invasion and for failing to stop civil war."

So why is it that a random killing spree in a university town in the States exercises our imagination more than the surplus of death served up daily elsewhere?

I was at a loss to understand why Virginia Tech upset me more viscerally than Iraq. I felt nauseous for the rest of the day after watching the BBC breaking news footage of the American university massacre; the wide-eyed, numbed survivors with arms interlinked, the photos of the killer. Why was that more upsetting to me than seeing the bombed shards of buildings in Baghdad, innumerable photos of blood-spattered children or the same dazed look of terror in Iraqi victims as had shone from the eyes of the American students?... Was it simply, shamefully, because the Virginia Tech students were "white"? I believe that a degree of unconscious racism possibly, inexcusably, played some part in my empathy weightings, just as it explains in some terrible way the horrifically protracted global inaction over genocide in Darfur. But that wasn't just it. It's a kind of racism, maybe a step-brother or a cousin. Both come from the same ancestors: prejudice, fear and a lack of imagination. But I'd argue this had more to do with landscape than it had to do with skin colour.

It was only when I thought about the slugs that I got it.

So. The slugs.

The house we rent is a characterful four floor Victorian terrace house, 5 bedrooms and a sweet overgrown garden. It's charming in a rickety, under-maintained but homely way and I love it. But recently the contented safety I felt within its four walls was disturbed. We discovered a criss cross of shiny slug trails one morning, decorating the carpet of our living room. The glittery remnants of a slug disco. Later, a dinner guest picked up her discarded handbag from the floor to find one of the small creatures had taken up residence. Yuck.

Slugs in themselves are not particularly pleasant of course but the disquiet and unease I felt was entirely disproportionate to their presence. I think the reason was: by crossing from their proper place - the dark, unlooked-for damp of a plant pot somewhere down the garden path - and somehow entering the manmade enclosure of OUR HOUSE, the slugs had monumentally broken the sequence and structure of things; the separation of outside and inside; garden and house; grimy, slippery animality trespassing on all our attempts at cleanliness and control. Thus they signalled chaos, loss of control, the futility of human efforts.

A familiar trope in good horror movies is the way the worst terrors of all are initially prefigured by small disruptions in the natural order. At the beginning of Hitchcock's "The Birds", the heroine is pecked on the head by a gull. It's only a peck but as she takes her hand away from her head, there is blood. So in the same way, the bizarre and unlooked-for entrance of slugs into our carpeted living-room signalled nothing less than the possibility of apocalypse.

What's this got to do with Virginia Tech and Iraq?

Here's the thing: I wonder if Virginia's tragedy was somehow more emotive for me, because it was the perfect example of the random and the uncontrollable entering the order we have worked so carefully to create, the order that defines western civilization, for whose sake we go to war, go shopping, go to therapy, go to Ikea. For whose reason we send our young people to the safe bastions of controllable chaos that we call universities.

Imagine your house. It's best to imagine the cheapest, smallest house you've ever visited actually. Imagine what that would look like to an alien who just landed on earth. It would look weird: millions of people, all building little arbitrary structures to hide inside, all putting up walls and making glass windows as a compromise with the sun. Spreading carpet where there used to be grass. Installing front doors with locks and doorbells and letterboxes.

All of this, this fortressing of ourselves, is designed to keep out A LOT. Not just slugs but also snails, foxes, magpies, burglars, axe-murderers etc etc.

Physical boundaries, walls and roofs serve to delineate the order we wish to impose on the world in general. Thus our architecture takes on an identity that is deeply linked to our sense of order and security. And perhaps one of the reasons we find it much harder to relate to Iraq or Darfur than to, say, Virginia Tech, is a kind of architectural racism. Because in our naive, ignorant understanding, we fail to recognize the order in unfamiliar architecture. Thus the images of disorder, of structures being broken in foreign lands, are less shocking and less meaningful than those in the places we recognize. At some level we think, breakdown in a desert is almost no breakdown at all. It's like the three pigs and the wolf blowing down the house made of straw. No-one's surprised.

Really I suppose I'm talking about relating to a way of life. If we can't relate, if we can't imagine inhabiting a place, "walking around in someone's shoes" as Harper Lee would say, then we don't care so much. Because our own interests are not under threat. It's hard for the average Londoner to imagine living in a village in Darfur or Iraq, even before the war, and that makes it a lot easier to distance ourselves from the victims who need our help most.

We should care. So what's the answer? In terms of Darfur, I wonder whether the best thing would be to make a film that emphasized those elements of human life that are familiar to as many people as possible. For that you'd need a documentary team to go and follow a family for a number of months, spending time recording all the common human experiences of family, relationships, the voicing of basic human needs, the great silence meeting those needs. That we can all relate to. We need to see the things we recognize at an unconscious level being threatened and then perhaps we will make the threat our own. And maybe, just maybe, we will be galvanized into action.

Wednesday 25 April 2007

slugs in the living-room and architectural racism

Tuesday 10 April 2007

Europe's Greenest City

Four out of five EU citizens inhabit metropolitan areas. So where's Europe’s greenest city? Likely suspects include Reykjavic in Iceland, Malmo in Sweden and Barcelona in Spain, all of whom were quick off the mark in instigating radical green reform. As the green city concept develops political cache, other metropolii are catching up, and nowadays many cities don’t just want to get green, they want to be the greenest of all. Events like the 2003 European Sustainable City Award (the winners were Ferrar, Heidelberg and Oslo) highlight the air of competitiveness that is beginning to seep into local environmental politics, while London’s Mayor Ken Livingstone chose this year’s World Economic Forum in Davos to publicize his commitment to making London “the undisputed world leader” in tackling climate change. But in Filtnib's humble opinion, the green crown must go to Freiburg: situated in Germany’s Black Forest, the city’s long-term embrace of all things green has single-handedly raised the eco-city game.

Freiburg is crucially a green party stronghold: in 2002 Mayor Dieter Salomon sailed into power with 65% of the vote, making it the first large green-governed city in Germany. But the burg’s eco-credentials go further back, and this is what makes it unique: in 1969, revolutionary transport regulations prioritized cyclists, public transport and pedestrians; the following year cyclepaths were introduced (they now run to 500km); and while most of Europe phased out its trams, Freiburg’s network was bravely being expanded. To put this in context, it's instructive to remember that right around this time, in 1971, French President Georges Pompidou was declaring, “the city must adapt to the car”. Good old Freiburg clearly wasn't listening: two years later the town centre was completely pedestrianized. Roll on 1991 and there's even a treat for the exercise-shy: a low-cost “environment public transport ticket” -just 44 euros a month will get you unlimited access to buses, trains and trams throughout the town and its 60km radius. Incredible. Mayor Salomon told me the highly successful scheme has since been copied across Europe, aswell as attracting research delegations from China and Japan.

Transport is just one element in the town’s sweeping eco-strategy. After the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 the council energetically pursued alternatives to nuclear power. Freiburg is now known as the solar capitol of Europe, hosting the headquarters of many solar research companies aswell as a Solar Training Centre. An innovative “solar village” has just been built within the new Vauban district of ecologically designed homes, where 50 solar houses all produce more energy than they consume. In 1996 the town had 274 square metres of solar cells; a decade on, solar panels span a colossal 11,223m. The 19 floor façade of Freiburg’s central station consists of 240 solar panels and the council even boasts a dedicated “solar information desk”.

Freiburg’s landscape is literally green, too: 42% of the surrounding area is under conservational protection and, as of 1992, any new construction on Freiburg’s municipal land must comply with a stringent low-energy standard, which caps the permissable energy requirement of a building at two thirds the national limit. Mayor Salomon argues that individual action is vital: "The real difference comes when people change their lifestyle, and this is also the real challenge. Thirty years ago in Germany there was only a small minority of people that lived in this way, and the majority laughed at them. Today, lots more people are thinking about it seriously." He adds that Freiburg isn't only concerned with limiting further damage; they’re now planning for a warmer world: "Freiburg will get a lot warmer, but we'll also have a more extreme climate. We expect flooding and storms".

One of Freiburg's favoured methods of mitigating the effects of climate change sounds somewhat like a new dance move: “greenroofing”. Fast becoming Germany's favourite home improvement, the process basically entails transforming roofs into vegetation layers that allow stormwater run-off, reduce energy costs and mitigate the urban heat-island effect. Freiburg's other big coup is a scrupulous recycling scheme: each household has 4 separate bins, and even kitchen and garden waste is composted. Consequently, waste disposal has more than halved since 1988, allowing Freiburg to win “best recycler” in the EU’s 2001 “Urban Audit” (80% of Freiburg's waste was recycled, compared to the European average of just 19%).

Despite the incredible achievements of this smallish town in the Black Forest, Freiburg's Head of Energy Klaus Hoppe isn't complacent, saying “There’s still a lot to do.” New targets are being set each year; right now Hoppe’s concerned with raising the 1.6% of power sourced from bioenergy to 2.7% by 2010. “Freiburg” literally means free city. The town’s eco-logic demands a lot of rules, but in the long-term it’s securing a more important freedom: that of future generations to inhabit a sustainable city. How long will it take for the rest of us to catch up?

Sunday 8 April 2007

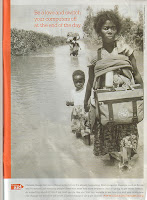

Climate Refugees

In 2002, a species of moth never previously recorded in north-western Europe landed in Sean Clancy's garden in Kent, England. It would become known as "Clancy's Rustic", and by 2005, dozens were being recorded on the English coast. Meanwhile, in a cliff-top garden at one of the most southerly points of England, Britain's Centre for Ecology & Hydrology had been tracking insect migration since 1982. Their results were startling. Hordes of rare butterflies and moths (lepidoptera), once found only in the Mediterranean and North Africa, were venturing into Northern Europe in unprecedented numbers. In January, Tim Sparks and his team finally published their findings: over 25 years, new species of lepidoptera entering Britain had increased by a staggering 400%. Sparks says the cause is clear: global warming. Just as Al Gore called the melting of the polar ice-caps "the canary in the coal mine", the new itineraries of migrating insects are a bright yellow warning - tangible proof the world’s natural order is undergoing radical change. As the earth warms, with butterflies already on the move, could people be far behind? "There’s little we can do to control immigration of new insect species," says Sparks. "And unless climate change is moderated, it’s likely to displace large numbers of humans migrants in a similarly uncontrolled manner."

Climate-induced migration isn’t new; it’s a survival mechanism as old as life on earth. Human mobility helped cultures sidestep possible extinction, and often worked as a catalyst for growth and evolution. It could conceivably bring dividends again, but not without cost. The Earth Policy Institute in Washington estimates that 250,000 residents displaced by Hurricane Katrina have established homes elsewhere - and will never return to New Orleans. In December, the worst Bolivian floods in 25 years submerged an area the size of Britain, making 77,000 families homeless. “Environmental refugees could become one of the foremost human crises of our time” is the grim warning of Norman Myers, an Oxford University environmental scientist who has been investigating the phenomenon for 15 years.

When Myers first wrote about the new breed of “environmental refugees” in 1995, he was dismissed as a hysteric. He certainly painted a scary scenario: 200 million environmental refugees by 2050, equivalent to two-thirds of the population of the United States; “a massive crisis; famine and starvation.” But the tide has changed, and his apocalyptic vision - “This is a major new phenomenon and it’s growing much worse, very rapidly” - looks increasingly plausible. British geographer Richard Black, who once suggested the concept of environmental refugees was nothing but a “myth,” now acknowledges, “There’s no question that one of the consequences of climate change will be an increase in migration… New research has been published, and I’d like to think I have a more sophisticated view on it.” Black is a world expert on migration, and a contributing author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s landmark report on the impacts of global warming, released yesterday. His concession, therefore, is significant.

But while the likelihood of mass climate migration is now acknowledged, there’s still an unnerving lack of consensus on what one of the broadest impacts of global warming might actually look like. All the experts agree serious research is required, and urgently. Richard Black concedes, “We don’t have any adequate data source for understanding this. Not one.” Myers, who found it difficult to obtain funding for his research, is first to admit: “I’ve done little research since 1995, so I just don’t know whether the figures have changed. Nobody’s doing on-the-ground analysis.”

What is lamentably clear is that the biggest losers will be those already most vulnerable: the developing world. Impoverished and climate-sensitive nations like Bangladesh and Kenya simply don’t have the resources to provide relief for displaced residents, and are desperately low on cash for the construction projects that could limit future damage. In 1996 Myers estimated that sea level rises induced by global warming would threaten the lives of 26 million people in Bangladesh, 73 million in China and 20 million in India. It’s from these areas that “climate refugees” are most likely to emerge, alongside drought-stricken regions of Africa. In the Mandera district of North-East Kenya, a four-fold increase of drought has already forced half a million pastoral farmers to abandon their way of life. In the village of Libehiya, houses are buried in sand dunes. This, according to a Christian Aid study last year, is “the climate change frontline”.

Where will climate refugees go? Black suggests European policymakers who imagine millions of new asylum-seekers probably have it wrong: “I suspect worsening climate won’t dramatically increase the number of West Africans coming to Europe. It will just increase the number of poor and destitute West Africans. The more desperate your circumstances, the more difficult it is to put together the money for a long journey. If you’re an impoverished farmer affected by a natural disaster you don’t just think, ‘Oh I know, I’ll go to Paris’. These people are living on a dollar a day; they don’t have a few thousand dollars stashed under their beds.”

The biggest losers will be those who never manage to earn the official title of “refugee” and are thus ineligible for international aid. As yet, there's no official recognition that environmental problems could alone justify “refugee” status. Myers complains the UN won’t rewrite the rules, “because their budgets are already overstrained, and they’re worried they’ll be swamped. Yet these are people whose governments are unable to safeguard their lives.” A UNHCR spokesman told me that although “we’re aware of it and it’s certainly an issue to watch,” the world’s pre-eminent refugee agency has no current strategy to deal with the threat.

The developed world will of course have its own share of losers. In 2003, a heat wave in Europe killed over 21,000 people across five countries. The IPCC warns that such sweltering heat will become increasingly common, with higher maximum temperatures and an average rise of between 1.1 and 6.4 degrees C over the next century.

Will this create “climate refugees”? Talking to experts like Myers and Black, it seems the answer pivots on a population’s “adaptive capacity”; crucially, inhabitants in the West can adapt more easily than people in poorer, less developed economies. France was able to spend an extra $748 million on hospital emergency services during the 2003 heat wave, later developing a four-stage plan canicule (for the so-called “dog days” from early July to early September). The Netherlands, after a 1953 flood killed nearly 2,000 people and evacuated 70,000, spent $8 billion over 25 years to prevent a recurrence; they now have a ministry devoted solely to the prevention of flooding - a department much consulted by U.S. specialists post-Katrina. Even supposing some people are forced to move, skilled and wealthy Westerners are less likely to become “refugees”, so much as “migrants” who are able to adapt, find work and rebuild their lives even if their home is destroyed.

Enter the winners. While areas like southern Europe will become increasingly uncomfortable weather-wise, there could be capital gains for the more temperate north. The Scottish government is sponsoring “Highland 2007,” a campaign to promote the Highlands as a desirable place to live. It’s an effort to arrest a declining population, but such marketing could become unnecessary if forest fires, heat waves and water shortages encourage northwards relocation from Spain, Italy and southern France. Underpopulated areas like Sweden - a country the size of California with a population of 8 million - not to mention Norway and Finland, could reap the rewards of an influx of skilled workers. And as urban heat islands like London, Paris and Tokyo turn airless and muggy, internal migration could usefully redistribute population from cities to the country.

Archaeologist Arlene Rosen from University College London is convinced there will be another category of winners too. She’s just written a book called “Civilizing Climate”. “Certain ancient societies adapted to climate change. For every society that collapsed, there was one next door that survived and got stronger because of it.” Rosen points to the first state society in China in 1900 - 1500 B.C., where incredible drought was nevertheless accompanied by a period of growth and expanding social organization. Archaeologists believe difficult climatic conditions led directly to an increase in trade, which created an economic upswing across society. And for around 5000 years, the Sahara was a green and fertile area, until it began to dry up in 4000 B.C., causing the large-scale migration of people to the Nile region, a key step in the creation of Egyptian civilization. “Humans are a resilient species,” says Rosen.

She believes history has lessons to impart, if we care enough to listen. “The bottom line we get from studying societies that survived climate change is that it’s in everybody’s best interest to share resources between the winners and the losers." Rosen says. "Political and economic cooperation to move goods and services around is vital. Wealthy governments today need to be convinced that it’s in their own interests to help the developing world.” Myers believes action on climate refugees could define our future. “Ten years ago I wrote a book-length report on this, I gave lectures, I talked to policy leaders and politicians. The global community just turned its back.” With climate change finally a priority on the international agenda, the experts hope the time has come for environmental refugees to get the attention they deserve. Perhaps we can then confront the brave new migratory world with foresight, not just fear.